Flexible packaging — any package that is flexible vs. rigid in form such as a chip bag or candy wrapper — has been on the rise since it came onto the scene. Data suggests it accounts for 19 percent of package sales (by revenue), which means well more than 19 percent of items we buy are in flexible packages. One major motivator: Flexibles carry a much lower cost per unit than rigid packages.

Indeed, the biggest mega-trend in packaging is, and always has been, cost reduction — and flexible packaging is the best driver of cost savings. In some cases, the format has also driven incredible improvements in consumer convenience, such as spouted pouches in baby food. It also drives sustainability advantages by using significantly less material than rigid packaging (for example, 97 percent than a glass jar). That saves both in extraction (mining materials and refining them) and transportation costs, as well as their associated environmental impacts.

Despite these breakthrough advantages, the major challenge associated with flexible packaging is the lack of recyclability.

In most countries, including the U.S., curbside recycling systems don’t want flexible packaging, as it is not profitable to recycle and processing it gunks up equipment. In countries where it is collected curbside (such as France), flexible packaging is still typically not recycled (for the same reasons). This dynamic is even worse in emerging economies (from Manila to India), where flexible packaging is even more prevalent.

In light of all this, most major consumer goods manufacturers (from Kellogg to Mondelēz) have committed that their packaging will be recyclable, compostable or reusable by 2025. So what’s the plan for manufacturers that want to stay in flexible packaging (which rules out reuse)? The scenarios can be broken down into three distinct approaches:

Do nothing: This will be where many small and midsize enterprises will land, simply because they don’t have the resources to make a shift.

Shift to compostables: Brands including Clif Bar to Off the Eaten Path are doing this, and you’ll see more. Switching to compostable packaging offers its own distinct set of challenges to overcome — more on that in a future article.

Move to "recycle ready" (or mono-layer) packaging to be collected via store drop. That is what we’ll explore today.

The most prevalent solution being enacted today is the third, moving from complex multi-layer packaging to mono-layer materials. The challenge is this material is not intended to be collected curbside for recycling. Instead, it is being taken back via front-of-store drop bins. That’s why it is critical to examine the role of retailers in embracing that option and how they might react with all this "recycle ready" packaging like to come into their stores in a few short years.

Some history. Back in 1991 (starting in Maine, and today in 36 states) grocery stores of a certain size were legally mandated to offer plastic shopping bag recycling front-of-store.

So let’s look beneath the hood to see which stakeholders play a significant role in that plastic grocery bag recycling system, as that is what the new "recycle ready" packaging will depend on:

Retailers: They are the most important actors, because they pay the bill for recycling plastic shopping bags, and it’s their physical locations where consumers can drop off plastic shopping bags for recycling.

Processors: Companies such as composite decking maker Trex (which manufactures its products from 95 percent reclaimed material, including recycled polyethylene plastic film) are the next most important actor in the system, as they set both the quality thresholds for actual recycling to occur and the associated economics. Companies such as Trex buy this material today to make high-quality recycled products. They are not legally obligated to buy it, nor are they obligated to recycle it if the quality that shows up is inferior for making their finished products. In other words, they will only buy and recycle what makes for a great quality finished product — at the right price.

Consumers: They drive both quality and volume through the system.

In talking with many major U.S. retailers (we won’t name names here), they generally don’t like being mandated to provide plastic shopping bag recycling (as it’s a cost center for many) and would prefer it to go away. This is evidenced by many lobbying for exactly that to happen, with their arguments strengthening in states such as New Jersey, which just banned the use of plastic shopping bags.

As pressure rises to invent and develop flexible packaging that is recyclable, the idea to simplify the packaging (a brilliant idea!) from multi-layer to mono-layer became the main focus. The key issue is where to collect that packaging after it’s used, as curbside recycling doesn’t want any form of flexible film.

And this is where the two stories come together: If a cookie wrapper is made from a mono-material, why can it not be collected in the same bins as plastic grocery bags are today in over 18,000 locations (as long as the consumer cleans and dries it)? So off went packaging companies, declaring victory. Their argument: As long as manufacturers move to mono-material (which they dub "recycle ready"), they can tell consumers to recycle it via the retailer store drop programs.

Purposeful brands trying to do the right thing, such as Bear Naked and Nature Valley, started as early adopters. With their leadership, moving to mono-material ("recycle ready") has become the main solution by organizations to meet their 2025 commitments for packaging recyclability. But will it work?

To answer this question, we have to consider what consumers will do, as they hold the keys to driving volume of collected material and, more important, quality of same. Imagine a world a few years from now, where your granola package tells you to recycle it at in-store drop-offs. Will you clean and dry it as the label asks? TerraCycle consumer insights research shows that most consumers won’t. And if you do this, will you assume this is what you should do with all other granola wrappers? In other words, if a Coca-Cola bottle screams at you to recycle it, is it a fair assumption that another beverage container that looks identical should have the same end-of-life solution, even if it doesn’t scream "recycle me"?

The likely outcome is that well-meaning consumers will simply take all of their granola packaging (no matter the composition) to store drop-off points without cleaning it out and then drying it. So volume will explode (versus just the single-use plastic shopping bags collected today), and quality will hemorrhage for two key reasons:

Content contamination: Economics for recyclers get worse when they have to remove residuation content — wet cat food, pasta sauce, shampoo, not to mention the invisible kind, such as oils and greases.

Material-type contamination: In a product category like granola bars, by 2025 you’ll have many packaging scenarios from multi-layer petroleum packages to various degradable package forms (from oxo-degradable to home-compostable) to mono-materials ("recycle-ready"). Again, economics get worse when recyclers have to separate out all these material types.

The result? In the best case, the cost per pound to recycle will increase dramatically. In the worst case, the buyers of this material, such as Trex, will simply reject it. Net-net, this means that the cost per year to the retailers, legally obligated to provide front-of-store shopping bag recycling, will explode (more volume at a much greater cost per pound).

So what will happen next?

My prediction (based on talking to the leading retailers in the U.S.) is that they will communicate on shopping bag recycling bins that they are only for shopping bags, as the law states, and not (for example) our shampoo sachet or cat food bag. Sound like a plan destined to fail?

I do think there is a solution. Moving to mono-layer materials is the best path forward, and if curbside recycling won’t accept it, the retailers are a great collection point. The key is doing it in a way that benefits all stakeholders. Here are some of my suggestions.

Don’t mix it all together: Where this has already happened (such as U.K. grocers) about 50 percent of the waste is recycled and at a tremendous cost. Instead, ask consumers to separate flexible waste into reasonable categories, such as compostables, food flexibles, non-food flexibles, pouches and shopping bags. Actual on-the-ground pilots, with retailers such as Walmart (who did that and other waste streams), show that they will.

Brands should fund their obligation: Once the materials are separated into reasonable categories, the cost to collect and recycle it should be funded by the manufacturers of those categories. This could be organized either as a market share-based payment (the supermarket charges brands based on their relative sales), or better yet, as a category leader opportunity in exchange for benefits such as incremental merchandising in stores.

As with any circular economy issue, it boils down to economics, and if we are going to ensure that the immense amount of flexible packaging that is produced every year has a responsible and circular end of life we have to follow the money and make sure the system is funding the right motivations. In this case retailers are in the driver seat and will make the important decisions.

Advantages of paper packaging

Advantages of paper packaging

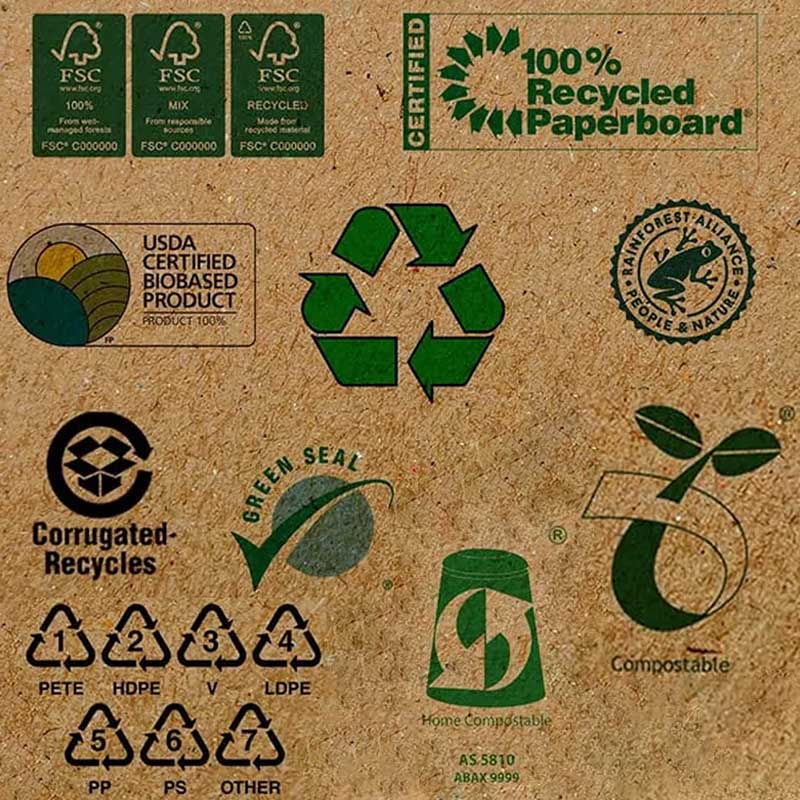

Get Clear About 22 Common Food Package Symbols Mean

Get Clear About 22 Common Food Package Symbols Mean

It's time to start preparing for Christmas

It's time to start preparing for Christmas

Why use virgin wood pulp paper as a raw material for food packaging paper?

Why use virgin wood pulp paper as a raw material for food packaging paper?